“So what kind of music do you like?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know? How could you not know what kind of music you like?”

“Elvis. I like Elvis.”

“Elvis. Elvis Presley? The King?”

“Yes, Munch.”

“The King? (Performing a passable Elvis move:) Has left the planet.”

“The man was a god.”

Det. John Munch (Richard Belzer) & Det. Ned Bolander (Ned Beatty)

“Smoke Gets In Your Eyes”; Season 1, Episode 8, Homicide: Life on the Street

The basement bar in Baltimore’s Lithuanian Hall carries Viryta, a thick honey herb liquor with East European roots served in thimble-sized plastic glasses for $3 a shot. It sticks to your tongue and the inside of your cheeks when you drink it, and you can’t help but wince, though the taste is warm and full.

They also sell Utenos and other imported Lithuanian beers, though I prefer to chase my shot with $1 Yeungling draft beers. The square basement bar where I’m standing at shimmers with a lacquer finish, and mirrors cover the four sides of the bar back. They reflect the silver bouncing from a twirling mirrorball above the linoleum dance floor that serves as the focus of the otherwise dark room. The only other source of light is a radiating fish tank and a bulb inside a pull-handle cigarette dispenser near the basement stairs, which lead up to the brighter floors on top of us.

On the lounge stage, under the mirrorball, Elvis is holding court. This particular Elvis hails from the 1968 Comeback Special, distinguishable by the full-body black leather jump suit he’s adorned in. A D.J., dressed in a tuxedo, accented by a seafoam bow tie and cummerbund, introduces the act, and then 1968 Elvis belts the first few lines of ‘Fools Rush In.’ The gaggle of middle-aged women sitting in thick wooden bar chairs around the stage flex and swoon, a natural, inherited response to so much leather-bound flexing and vibrato.

Walking the square dance floor,1968 Elvis works to force a connection with every woman in the audience, grabbing their hand, lightly straddling their leg as he sings directly to them. The performance edges on creepiness, but I give him credit for making it work in the end. The wives love it, the men chuckle a bit under their breath. At the bar, the younger couples try to soak this in the cultish scene.

This 1968 Elvis understands what he’s doing, his appeal, that Apollo-like machismo Elvis impersonators radiate. This Elvis is an experienced hand at the floor.

Standing behind me against the wall, a 1970s Elvis, wearing the iconic white leather jumpsuit adorned in rhinestones with a black-off color shoulder cut, analyzes his contemporary work the stage. Across the room, Lounge Lizard Tuxedo Elvis, Evangelical Blue Jean Elvis and 8-year old Rockabilly Elvis also keep their gaze on the floor show. They, too, are veterans of the pink spotlight. This is it, this floor, that mirrorball above, the women finding energies they hadn’t tapped since Tiger Beat and record hops. They talk Elvis. They dress Elvis. They live Elvis.

The 18th Annual Night of 100 ELVISes, a Baltimore tradition akin to the Preakness or Defender’s Day, is in full swing.

———————————————————-

“An Elvis man should love this.”

Mia (Uma Thurman), Pulp Fiction

The Baltimore Hon, that beehive and leopard print panting-wearing Mama who stalked Eastern Avenue in days of White Baltimore yore, is a known entity. But what about the Baltimore Elvis Man? The obvious complimentary figure to lady Hon, The Elvis Man at one time numbered in the thousands here in Charm City, radiating grease lightning and heart-felt emotion wherever he went.

The Baltimore Elvis Man is not an impersonator, by any means. He exists instead to pay staid homage to the King. He may own the old records, and he may have a velvet painting above his mauve couch, but the direct connections ends there. Instead, he attempts to embody that Memphis feel, a working-class greaser of his time and place.

When I was little, my parents rented our upstairs apartment to Elmer, a local Hampden mechanic. Elmer was a true Baltimore Elvis Man. He drove a coffee-colored Cadillac, worked in a car repair shot, wore tinted sunglasses and greased his hair with palm aid. He owned a white teardrop Mybelle telephone, a desktop-sized suit of armor that was really a cigarette lighter, and a toilet seat embedded with a beach diorama, with sand and starfish and plastic seahorses gayly frolicking underneath the encased plastic. He vacationed in Florida to meet women and to work on his tan in the cheap Gulf Coast beaches. He dated Hons. On my birthday, he would give me two rolls of nickels, fake punching me in the stomach before revealing his gift.

There used to be an army of Elmers in this city. Time has dwindled their numbers, but the sheer existence of the Baltimore Elvis Man illustrates that, for whatever reason, The King has a seat firmly among the major deities in Baltimore’s icon hierarchy, nestled somewhere between Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas and beer mascot Mr. Boh. Velvet Elvises hang on wood-paneled walls across Charm City, just above the nicknacks, next to photos of the pope and Cal Ripken, mostly in old row houses, mostly in last dying veins of city’s working-class white neighborhoods in East and South Baltimore.

Elvis love is not all reverent. Kitsch is a chief commodity in Charm City, and Elvis is valuable within the economy. Down in Canton, a wooden statue of the King sits in the front of Nacho Mama’s, a Tex-Mex restaurant with deep Bawlmer sentiments. On special occasions the owners paint the statue —purple for the Ravens’ playoff games, green for St. Patrick’s Day, Orange and black for the Opening Day of baseball. A wall of velvet paintings hang in the back dining room. Similarly, Walters Museum Director Gary Viken is a famous King of Rock & Roll aficionado, spreading his tongue-in-cheek thesis that Elvis should be canonized as a saint.

If, then, Elvis is worshipped as a religious figure in Baltimore, than the “Night of 100 ElVISes,” an annual two-day party held the first weekend of December, in the height of the holiday season, is his annual Feast Day in Charm City.

Spread through three floors in West Baltimore’s Lithuanian Hall, the event, ostensibly a charity fundraiser for the Johns Hopkins’ Children Center, features overstuffed amounts of Elvis and Rockabilly entertainment. The shows are split between three floors of fun; a full-band stage in the main hall where the major action takes place, the Elvis Lounge in the downstairs bar which features all Elvis impersonators, and the third floor Jungle Room upstairs where the hip cats go to cut a rug.

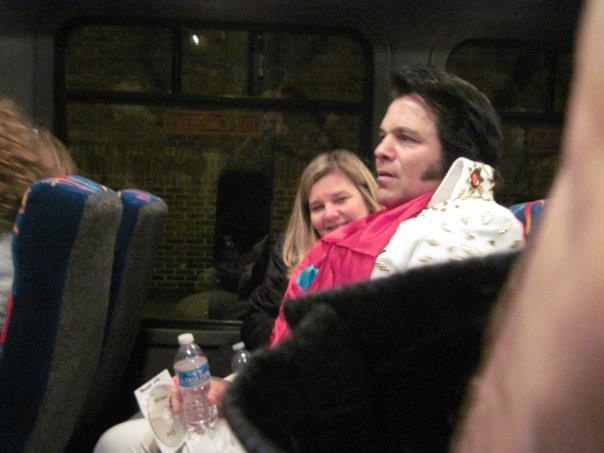

My girlfriend Sam and I sit on the floor of a shuttle bus filled with Elvises from a North Baltimore hotel, home base for the weekend off-site frivolity apparently. She is dressed in full Old Hon regalia; leopard skirt, black fishnet stockings, and hair piled high on her head. Instead of hairspray, she stuffed her quaff with a bathroom loofah sponge, which gives her ‘do extra bounce. I wear my cowboy casual with a dark blue suitjacket and vest, accented with a silver and pearl bollero tie. Elvis songs drift through the cab from the shuttle’s stereo, and the middle-aged crowd in the seats drink beer from bottles.

Soon, we arrive in West Baltimore. The hall is the size of a high school gymnasium. In the back of the room, an elevated wooden stage, bathed in gold house lights and a giant sign with ‘ELVIS’ spelled out in light bulbs, serves as the main hearth of the Elvis evening. The floor is split between those who bought reserved tickets-mostly elderly, hardcore Elvis fans- and the standing room section where the middle-aged and 20-something hipsters float about. A projector beams a huge Young Elvis icon into the crevasse of the hall’s East Orthodox-inspired dome. There’s a Charm City Cake on stage, carved to represent a movie theater, and against the wall a row of volunteers pour local Heavy Seas beer into clear plastic cups. To the right, a side carnival is set up, complete with a caricature artist and an Asian dominatrix wearing a leather g-string with ‘Jailhouse Rock’ scrawled across her exposed butt cheeks.

On stage Fat Rockabilly Elvis belts ‘Jailhouse Rock’ into a silver stand-up microphone. A few of the young hip couples trot about, until an older couple decides they’ve had enough and steal the floor. They are both in their mid-late 60s, lithe, and wear matching pink button-down shirts and khaki pants. They are accomplished swing dancers, and burn the floor with twists, twirls and lifts. A circle forms around them, and the crowd starts clapping and hooting them on. Fat Rockabilly Elvis continues to swing and sweat through his set, throwing lip curls and sweat soaked silk scarves to the masses.

The dancers continue to twirl, and the crowd foams up into a frenzy, until finally the music ends and the dancers end on the downbeat, the husband lifting his wife to sit on his hip. The room is exhausted, and its still early yet.

—————————————————————————

“We killed him, you know? Yeah, we killed Elvis. It’s just as if we’d taken a gun and put it to his head.”

Det. Ned Bolander (Ned Beatty)

“Smoke Gets In Your Eyes”; Season 1, Episode 8, Homicide: Life on the Street

Elvis’ last performance in Baltimore was in 1977, three months before his untimely death, at the Baltimore Civic Center. About halfway through the show, the King left the stage to rest a hurt ankle and ‘nature calls….and you can’t do nothing about nature.” The concert is considered one of the lowest points in Elvis’ career.

Tonight, though, the King was alive and well in Charm City. He sang a duet with Santa while a dozen chubby belly dancers wiggled around him in a circle. He purred over a thumping beat while a hip hop dance team from Villanova cut splits and spun on their heads in the basement lounge. he crooned with the Belvederes review. He posted up with Sam and I for pictures, his back adorned with golden rhinestones set in the formation of an Aztec sun.

Now, on the bus, on the way home, the King comes to life one last, exhausted, time. A dozen Kings are here, riding the shuttle back to the North Baltimore hotel, up Interstate 83, past the red and green glitter of the Steiff Silver lights. Sam is passed out on my shoulder, the loofah that held her hair together flopping gently on my shoulder.

A Younger 70s Elvis calls the shuttle to attention. “Just so everyone knows, the Gracelanders are going to be killing the bar until 2 a.m. tonight, and no one parties like the Gracelanders!” The other Gracelander Elvises grunt in confirmation.

Over the shuttle speakers, the King’s rendition of ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ ques up. And slowly, the Elvises start to come alive.

“When you’re weary…….feelin’ small. Wwwwhen tears, are innnnn your eyes…Ah will dry’em all.”

Fat ’60s Gracelander Elvis. Evangelical Elvis. Younger 70s Elvis. They all pitch in.

“Ahmmm on your side, OOOOh when times get tough!….ANNNNND FRiends just CAN’T be found….”

They are all channeling it now. Elvis has left the Lithuanian Hall. He’s here now, in the seats of the bus grinding its way north. The Elvises work together, putting gospel into every verse.

“LIKE A BRIDGE ova troubled waters, I WILL Lay me dooooooooooown! LIKE A BRIDGE…!”

As voices rise, the shuttles rolls into the darkness, up the interstate, into a Baltimore winter’s evening.