Fire was a potential threat atop Mount Diablo on this day. There was a sign posted at the entrance of the state park warning of the dangers of the dry climate. It’s appropriate that, roughly 1,000 meters above sea level and a half hour east of Oakland, fire could be a threat. Up here, the primitive dangers still hold sway.

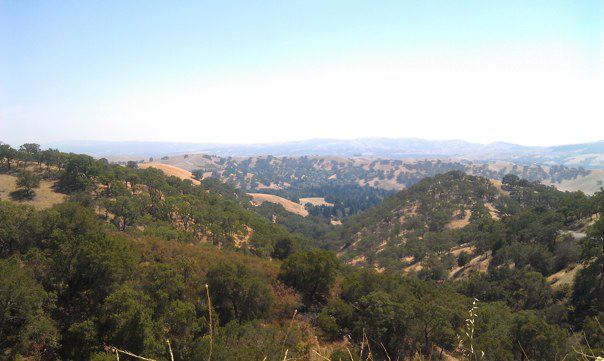

I’ve been to San Ramon Valley before, but this was my first time scaling Diablo. I couldn’t resist this time, the mountain’s prehistoric heft overwhelmed me. The road to the summit winds like an unraveled ribbon, dropped onto the edges of the mountain. I drive my Mini-Coop to the base of the summit, pull my car over and step out in to the air. Below, the San Ramon Valley stretches east to the Altmont Pass, along the full Diablo range all the way to Yosemite. Caramel sage brush cover the landscape. To the west, supposedly, on a clear day you can see San Francisco. The haze blocks any view of the city though.

For extinct Miwok and Ohlone tribes who lived in its shadows, this 3,000 foot peak was the point of creation, where the Coyote creator and the Eagle-Man made the people of the world. Later the Spanish called it Monte Del Diablo or “thicket of the devil”, a mysterious place where the natives magically escaped the conquistador hunters.

A redtail hawk circles over head and a murder of crows shoot off into the distance and then nothing else. Wind whips crisply over the brown summer grasses. The silence is suffocating, like a heavy humidity, seeping into my lungs. My skull is dizzy, burnt but the unencumbered sun hanging above me.

I slide back into my car. It’s time to leave. This place was named Diablo for a reason, and I will respect that.

—————-

Los Azteca is my favorite taco shop in Cotati, California, a sleepy college community in the heart of Sonoma wine country. The meat is stewed until tender, chopped coarsely, laid heartily in a pile of corn tortillas (gringos never understand, but you have to layer the corn tortillas to make it work) and augmented with cilantro, onion and a squeeze of lime.

There’s a mural painted on the wall at Los Azteca. It pictures an Aztec warrior, adorned in a loin cloth and a magnificent feather-plumed headdress, cradling a Hispanic woman with European features, wearing a flowing white dress. The warrior’s body is tanned and chiseled. His expression is mournful. The woman’s eyes are closed. In the distance, two snow covered mountain peaks rise skyward, shadowing the couple.

The piece, from the Mexican legend “Popocateptl and Iztaccihuatl,” is effectively melodramatic, drawing inspiration from both Catholic religious iconography and grocery store romance novel cover art. It is also ubiquitous throughout Mexican taco shops in California. Thousands of taco stands and bodegas have this mural on the wall.

According to the story, which stretches far back to pre-Columbian times, Popacatepetl and Iztaccihuatl were lovers born into the Tiaxcaltecas tribe. Long oppressed by the Aztec Empire, the chief of the Tiaxcaltecas decided to fight for freedom. Popacatepetl served as one of his finest, most fierce warriors.

This chief had a daughter, Iztaccihuatl, who was the most beautiful of all princesses. She in turn professed her love for Popocateptl. The two were soon married, then Popocateptl headed into Battle with Aztecs.

With news from the fighting hard to ascertain, a rival suitor of Popocateptl, the cowardly Tlaxcala, convinced the princess that her lover had died in battle. Distraught, Iztaccihuatl died, crushed by her own grief.

Upon his return from battle, Popocateptl learned of his lover’s demise. In his grief, he wondered village, both mourning her tragic death and devising a way to honor her. He eventually decided to build a great tomb, piling ten hills together to make a giant mountain, atop of which her body would rest. When he completed the arduous task, he placed her body at the mountain summit. He then knelt by her body, intent to keep eternal vigil. Eventually Popocateptl and Iztaccihuatl became volcanos, standing together looking over Mexico City.

Popocatepetl is still an active volcano, and when it erupts, it is said the old warrior is rekindling his grief for his lost Iztaccihuatl.

—————————————-

At first I thought it was smoke from a nearby forest fire. California is a tinderbox in the summer, and residents constantly live under the threat of major infernos caused by a causal cigarette flicked into the dry hill grass. As I drive closer though, along U.S. 101, I realized this was the True Fog of San Francisco.

During summer in the Bay Area, warm air blows in from the central Pacific Ocean, then moves over the cool water of the California Current, which flows just outside of San Francisco bay. The two elements, wind and water, form this robust fog, which rushes across the bay in a cloud wall, enveloping the region.

The fog tumbled over the hills outside of Sausalito at breakneck pace. Riding U.S. 101. I pulled into the cloud mass. Car lights burned through the thick precipitation, but I could only see a vehicle or two ahead of my own. The pace of traffic is deliberate; cars idle, a driver yawns in the sedan to my left.

Ahead on the 101, I make out the shadowy outline of the Golden Gate Bridge. It is a hulking structure, rising up from the bay like a primordial sea creature woken from its watery slumber. Its suspension cables reach out at me, long and nubile, like tentacles from a giant squid, desperately attempting to pull my car into its shrouded bosom.

I drive across the bridge, crawling into the endless void, hoping desperately to find civilization on the other side. High above the grinding traffic, the Golden Gate Bridge’s iconic burnt orange towers disappears into the fog, the peaks shrouded in the bellowing abyss.