Once or twice a year, I buy a roundtrip bus ticket and spend a long weekend living out of my Aunt Frankie’s New York City apartment. It’s located on 87th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a block off Park Ave. and a short walk from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Central Park.

The apartment is a strange place. My aunt is an amateur antique’s dealer, and her collection overwhelms the space. The living room features 19th century European furnishings, ceiling-tall wardrobes, tapestries from the Middle East, Impressionist prints, cabinets stuffed with crystal and fine china, Tibetan folk art, pottery and body-length lead mirrors. In the center of the room, two cobalt blue roosters lamps flank a red velvet fainting couch. In the bedroom, two full-sized mattresses sit high atop frames made of mahogany. Japanese screen art covers the walls, and a bookshelf near the door is stacked with the entire collection of Frank Baum’s Oz series.

However, the apartment is also the perfect launching pad for a New York weekend, since its just a block away from the Lexington Ave. Metro station, which provides easy access to the 4-5-6 subway lines that cut through Eastside Manhattan. With a room accounted for, New York becomes a remarkably cheap vacation. There’s the $35 for the Bolt Bus roundtrip ticket, and another $30 for a 7-Day Metro pass. With those two items, the city opens up to you.

My girlfriend Samantha and I spent a late August weekend in New York, riding the trains to the edges of the five boroughs. Early on a Saturday morning, we rode the 4 train to the C train, which dropped us off in DUMBO, a neighborhood that sits between the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges on the other side of the water from New York’s Financial District. Families meandered around a refurbished antique carousel. A stained glass water tower designed by artist Tom Fruin sat high above on one of the rehabbed warehouses, the sun illuminating the aqua, maroon and nectar panes. Tugboats and barges passed along the East River. While walking through a waterfront sculpture garden near the intersection of the two bridges, we pleasantly and awkwardly found ourselves witnesses to a surprise marriage proposal. The woman cried and we walked on.

That same afternoon, we rode the N train to Coney Island, located on the southern end of Brooklyn. There, we gorged on Nathan’s hotdogs and fries, then walked the boardwalk and listened to a salsa band play while Latino families danced together near the beach. A cornucopia of languages buzzed our heads — Russian, Spanish, Mandarin, Korean, Portuguese, Arabic. Children splashed about in the Atlantic Ocean under gray skies. Amusement rides like the Wonder Wheel and the historic Cyclone roller coaster towered over the beach like Manhattan’s skyscrapers, while a row of massive concrete housing developments shadowed those rides, like an ancient mountain range.

A fishing pier stretches out into the water off the Coney Island beach. Puerto Rican and Asian men stood shoulder to shoulder along the edges, cutting chum on the wood planks and reeling up croakers and small Atlantic sea bass and chucking them into coolers filled with crushed ice. On this particular day, a tiny Latin girl in a purple Disney shirt was beating the men at catching fish. “She’s the best damn fisherman of all them,” a black man wearing a faded blue Navy service baseball cap said. He stood in front of a makeshift bait shop he set up at the far end of the pier. Next to him, a Puerto Rican man in a basketball jersey blasted Latin music from a speaker and boombox set tied to a metal push cart.

That evening, The Q train took us through central Brooklyn, to Prospect Park in the heart of the borough. Hundreds of people were hanging out in the park, throwing frisbees, picnicking and enjoying the late summer weather. We passed two weddings, one a Great Gatsby style shindig held in the Audubon Center, and another a more laid back affair that took place in one of the park’s indoor pavilions, right in the middle of hundreds of Brooklynites. Later in our walk, we stumbled on a third wedding party set up in the shadows of the massive Grand Army arch, located at the northern tip of the park. Flanked by statues of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Grant on either side, a tall man in a white tuxedo with tails posed with his bride for photos, their white stretch Humvee limousine idling a few feet away.

The following Monday, on opening day of the U.S. Open Tennis Championships, we jumped on the 7 train to Flushing, into Queens. Perched high in the stands, we watched James Blake, Mardy Fish, Melanie Oudin and other tennis sorta-greats play the early rounds in historic Louis Armstrong Stadium. On the back courts, international players squared off, with their New York-based fans encouraging them in their native languages. One man, dressed as a boxing kangaroo, cheered on his Aussie compatriot. In person, the women tennis players were both imposing and impossibly beautiful. We even suffered through a U.S. Open tradition, the inevitable rain delay. Later though, an evening sunset baked the crowds that made it through the early rough patch to stay and watch final session matches.

Through the weekend, we would hop the L train to the Bedford Ave. stop, into the heart of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood, the capital of American Hipsterdom. In the day, the streets there bustle with young, mostly white kids wearing the traditional wardrobe — tight jeans, cut-off shorts, sleeveless striped beatnik t-shirts, big sunglasses, vintage ball caps, mustaches. At night, We spent time with Baltimore friends in Williamsburg’s basement dives and rooftop bars, the glittering lights of Manhattan serving as the backdrop.

Without these subways, we could not have indulged in New York in the manner that we did. It’s amazing how the sheer weight of humanity keeps those trains moving at 10 minute intervals 24 hours a day. They are the city’s blood cells, transversing the veins of the massive metropolis. And because of that, they allow anyone to be of New York, to find their own corner of the city and carve out an existence.

These trains move because New York wills them. As a visitor from a city where isolated neighborhoods are a way of life, you get a whiff of that freedom and its just enough to depress you during your Bolt Bus ride home.

———————————————–

New York is one of the United State’s —and, really, humanity’s— greatest achievements. It exists because of man’s need to push himself and see how the species can thrive together in a tight space while reaching upward into the heavens.

I would like to live in New York I think. Part of me is enticed by the idea of reinvention, to find the canvas where I could change my personal image and life decisions and intellectual mentality. Tattoos, slick haircuts and enhanced ethnic dating regimes are just more achievable in the Big Apple.

Another part of me would just like to live in a city where I can attend a basketball game without driving through the Eighth Circle of Hell that is the Washington D.C. Beltway during weekday traffic. I’d own Brooklyn Nets season tickets tomorrow if I knew I could jump on the Q train to attend a game. Or maybe hockey games, or any full sport that’s not just baseball or football, really. Die hard fandom is inherited, but there’s something enticing about riding the rolling waves that a city with a full allotment of sports teams gets to do.

Another side of me would just like to give up a car and ride the rails all day.

There are days when the shadows kick in and I find Baltimore an intolerable place to live. I would love to turn my back on my hometown. In my lifetime we’ve suffered three decades population decreases. Roughly 50% of the city’s residents live in poverty. A good swath of my compatriots are involved in the drug game, which perpetuates a culture of violence and lawlessness that has hampered attempts at true urban renewal. The blue-collar white enclaves dominate the ring of suburbs around the city, cultivating a racist, homophobic and culturally backward view of life. Remarkably, for two groups that are very much aligned in many ways, the cultural chasm that separates the poor and middle-class white community and the poor and middle-class black community in Charm City is still very deep and very wide.

Meanwhile, Blueblood Baltimore washes its hands of both communities, throwing up barriers both concrete (roadblocks at the entrances of the city’s more posh neighborhoods) and ones that live along finite, unspoken lines (streets you do cross, streets you don’t cross). Another contingent, the yearly influx of college grads, spend their five to 10 years living in the waterfront neighborhoods, drinking and playing kickball before shuttling back to the ‘burbs. Any gains the city has made in attracting immigrants, outside of a few blocks in Upper Fell’s and along Eastern Ave.,still haven’t added up to much. The majority of our municipal workers —cops and firefighters especially—abandoned the city they work in long ago and live far out in the exurbs.

These lines, this Balkanizan of our neighborhoods and communities, makes consensus impossible. In New York, you can not ignore the will of eight million people. Shit must get done. In Baltimore, there just isn’t enough humanity to push an agenda forward. Arcane political processes bash heads with arrogant entrepreneurship. Racism and classism strangle initiative. Malaise and radicalism trumps educated leadership.

So, we Baltimoreans are plagued with shitty public transportation. A Light Rail runs North and South with no natural connection to East and West. A subway shoots out to Owings Mills and back, with no thought of expansion. There aren’t enough buses to make that system timely for daily commuters, and the streetcars are long gone.

Cynically, this is the way the regional community likes to keep it. The harder it is for interlopers to find my neighborhood, the better. That’s why communities fight Light Rail extensions and the development of a Red Line subway connecting Catonsville to Dundalk. This is why bus stops along the MVA lines are removed without notice. In New York, the train takes me into new corners that are, for the most part, welcoming. Baltimore revels in isolation. You are not wanted here. Get out.

—————————

So, yes, part of me would like to run away to New York. But, I also believe in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s life view. No one can truly unfetter themselves from the past, no matter how much they make or how far they run from their old home. Sometimes your DNA is what it is.

Last Thursday, on a humid September evening in Baltimore, the Orioles baseball team returned to Camden Yards to kick off its most important home series in 15 years. Over Labor Day weekend the surprise Birds finished 4-2 on a tough road trip against the Yankees and Toronto, putting them just a game out of first place in the American League East. On this day, then, the Orioles would face off once again against New York in the first of a crucial four-game home stand.

The Orioles, in an eerie parallel to the city they call home, have through my adult life been mired in a deep funk of failure. Apathy, mismanagement and an inability to change with the shifting winds of the game’s economics turned a team with a proud tradition —three World Series, six pennants, multiple MVP and Cy Young winners— into a sad bottom-feeder franchise.

Somehow, though, after a decade and half of losing records, the Birds turned it around this year.

Major momentum helped build up this Thursday night game. As part of a season long series honoring former legends, the Orioles invited Hall of Famer Cal Ripken Jr. back to Camden Yards to unveil a bronze statue sculpted in his likeness that will stand next to similar statues of the O’s six other Hall of Famers in an outfield courtyard. Thousands of Orioles fans initially bought the tickets to take part in the Cal spectacle. However, with the team sitting a game behind first, with a chance to take the division, the tenor of the evening took on a new shape.

The sold out crowd of 45,000 was fired up and hungry for Yankee blood from pitch one. The traditional shouting of the “O” in ‘O, Say Doust that Star-Spangled…’ during the National Anthem shook the stadium. An explosion of cheers echoed off the Warehouse after catcher Matt Weiters crushed a three-run home run into the left field bleachers to take a 4-0 lead in the bottom of the first. When they O’s were pitching, during 0-2 counts, the crowd stood and banged the seats and clapped loudly, and then exploded again when starting pitcher Jason Hammell hit strikeouts to end the second, third and fourth innings.

There were, remarkably, true Baltimore faces in this crowd, the Bubbys and Donnys and Chrissies and Jessicas of Greater Charm City, making the trip to Camden Yards from Dundalk and Hamilton, from Towson and Pigtown. Their faces were fat and red, shimmering in a special sweat that only light beer and Mid-Atlantic humidity can produce. There were, for a sport that’s done its best to alienate an urban audience, more African-Americans in the crowd than usual. It was good to see everybody together, enjoying each other’s company for once.

In the top of the eighth, the Yankees made their run, notching five runs off Baltimore relievers Dan Wolf and Pedro Strop. The old Orioles fandom fears started to sink in. New York, with their $200 million roster stuffed with veteran players, was going to make its inevitable comeback.

Then, in the bottom of the eighth inning, with two strikes on him, Orioles centerfielder Adam Jones, this year’s unofficial team captain, golfed a home run into left to push the O’s to a 7-6 lead. Two batters later, first baseman Mark Reynolds smashed a two-run homer to left center. Then, as a nightcap, DH Chris Davis slapped a homer into right field into the standing room only section. Boom. 10-6 O’s.

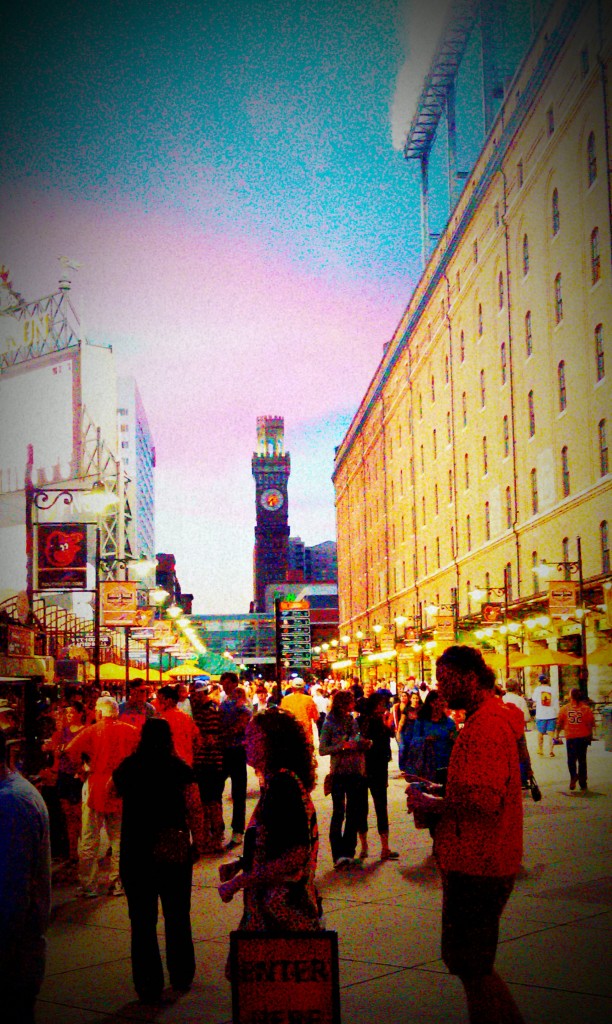

The roar of the crowd echoed all the way to Washington. I smashed hands with my neighbors and threw my girlfriend into the air. Over on Eutaw Street, the standing room only section turned into a mosh pit, with Orioles fans jumping together in pandemonium.

My provincialism set in. Fuck New York. It’s a suck hole where the elite financial barons live, that pompous oligarchy that helped dismantle my city’s industrial economy, fund suburban exodus and, more recently, crashed a promising housing market that drove so much revitalization in the late ’90s and early ’00s. The Big Apple thrives because it helped destroy Mobtown.

There is no way to exact revenge in reality, or turn back the economic hands of time. There, is though, a cathartic joy to be found in watching 45,000 of my brothers and sisters laugh at Gotham’s misery.

Orioles fans remained in Camden Yards through the last pitch of the game, and when closer Jim Johnson ended the contest on a called strike three for the 10-6 victory, the people still stayed and cheered, not wanting the evening to end. On the walk way out of the upper deck, fans chanted O-R-I-O-L-E-S. Near the railing, a middle-aged Baltimore dude walked up to a cop and said “That was the best damn baseball game I’ve gone to in 15 years!”

The crowd dispersed, still flush with victory. I walked toward the Inner Harbor, back to my office parking garage. A few blocks away from the stadium, in front of the city’s convention center, I walked passed an older African-American man with a salt-and-pepper beard begging for change. He was strapped in an automatic wheelchair and wore a black Orioles shirt. I pulled out my wallet and put a dollar in his soda cup. He was a Baltimorian, after all, and so am I, and he deserved my help.

And then I walked to my car and drove home.